Author Archives: js_admin

What are whole systems?

This post, is by way of capturing my ongoing conversation with Roger Duck concerning the meaning of ‘a whole system’.

The word ‘system’ means many different things to different people, so its worth an exploration of what we mean by it:

There is an even more fundamental communication issue than terminology at work when it comes to ‘whole systems’. We all have underlying assumptions, which we rely on being unspoken but shared when communicating with others. One such common assumption is that the world, and everything within it, is made up of ‘things’ – people, houses, forests, cities etc. If I think about a ‘thing’ it tends to conjure the image of a static object and I am drawn into examining it. To understand ‘whole systems’ it is necessary to suspend the idea that ‘things’ are the fundamental building block for a moment or two and try thinking of the world as being made up of ‘happenings’ dynamic processes which are going on all the while, overlapping each other and with complex patterns of interaction taking place between them.

I find the simple trick of adding ‘ing’ to a word can help change my thought patterns: so not boat but boating, not rain but raining, not breath but breathing. OK it doesn’t work for some words, so you may need to add an ‘ing’ word as in: not violin but playing the violin. ‘Ing’ words tend to bring along a context with them, so for comparison, if I think about rain I might focus on a rain-drop in isolation, whereas, if I think about ‘raining’ I can’t help but imagine a broader and diverse context: so, raining in the garden and bouncing off the path and refreshing the plants or swelling a river, or falling from a dark cloud or filling a reservoir etc. Thinking about the world in terms of ‘interconnected happenings’ causes me to consider the uncertain future based on a broader context than the thing itself: will it stop raining before I want to go out? Will this river breach its banks and flood? I am not drawn to look inside the thing ‘the raindrop’ but to consider its effect on everything it has contact with and that is in contact with it. If you can get the knack of looking at the world through this particular pair of spectacles, then envisaging ‘whole systems’ follows naturally.

So getting back to the word ‘systems’, what are the other meanings which need to be distinguished? A very common one is a ‘technical system’. In a computer industry context ‘the system’ is usually the combination of software and hardware and communications technology that accomplishes a set of specific tasks on behalf of some users. Note the people involved (the users) are not part of this system – the system is ‘a thing’ which can be defined and the users with their unknowable possible range of actions are excluded from the system, so that the technical functioning can be specified exactly and the system can operate regardless of the context it is being used in.

This concept of a technical system, distinct from it users leads on to another possible misunderstanding of the term system. Technical systems sometimes fail, because they have not been considered as a whole. They may have been segmented into components at an early stage, with rudimentary inter-communication capabilities and over time these components have individually evolved to do new and different things, so they have become like a jigsaw where the pieces have changed shape independently destroying the overall picture. This overall picture can be termed ‘a whole technical system’ as opposed to ‘a set of components’ which may or may not fit together well.

Another common use of the term ‘system’ is to identify a clerical procedure, e.g. the objective setting and review system. This, as in the technical use, excludes the people who perform the procedure. Such procedures can be defined, clearly and unambiguously, and act as a definition of what happens regardless of the context in which they operate. This idea can then be scaled up to a set of such procedures, so an administrator might talk about ‘the whole business system’ meaning all the office procedures combined and operating across all departments.

Another use of the word ‘system’ is in thinking, as for example a system of philosophy based on a number of assumptions and building into a ‘whole system of thought’. Again the system can be constructed and operates regardless of context.

There are no doubt many other examples: economic system, political system etc. which could embrace the term ‘whole system’ to mean the unification of a number of components within a bigger picture. The key difference between all these examples and ‘whole system’ as used here is that all these examples limit the domain of interest and can be described by the term ‘systematic’. Our use of the term ‘whole systems’ expands to include all relevant domains and to understand how aspects of different domains interact together within the current context and in potential futures.

So finally looking at ‘whole systems’ as used in this post – there are some clear differences emerging from these examples of other uses of the term.

Whole systems, in the way we mean the term, are:

- Dynamic and unpredictable – they always include everything (including people) that play an essential part in the achievement of the systems objectives – and people always introduce unpredictability.

- Operating within a context and cannot be understood without their context

- Communicating with their context in a fully interactive manner, proactively and reactively and co-operatively, responding to feedback and learning – again introducing unpredictability. Their component systems are also interconnected and interact together in proactive, reactive and co-operative ways.

- Multi-domain – including all aspects involved in addressing their objectives, and so can be said to be holistic and in that sense ‘whole’

- Can be described by the term ‘systemic’

So finally, given this broad definition of whole systems, how can any individual get a good understanding of them? The answer is that understanding does not come from logical deduction in one head, but through sharing and combining the different perspectives from all the stakeholder viewpoints. Our approach to addressing this is one of developing shared models of interacting “happenings” that reflect the underlying dynamics of the system of interest in-context. This is done in a way that enables everyone to understand how their own perspective on the system relates to the perspectives of others.

What would be the impact of Customer Centric Action on Service Providers?

This post is built on the previous post on Customer Centric Action on Need.

Practical transformation is built on analysis of local needs and constrained by the sum of resources available to local public, voluntary and community organisations and the citizens themselves. Commitment and desire for change has to emerge within each community and its service providing organisations. It requires strategic design and agile implementation. This post is a work of imagination provided to illustrate what could transpire.

This post imagines how Customer Centric Provision might support transformation in Service Providers, including local authorities. It does not address the delivery of the straight forward individual services within the scope of each organisation’s purposes or specific statutory requirements placed on the organisation.

The community governance structure and its representatives are now responsible for overseeing the meeting of the needs of its own community, both in terms of future provision and today’s delivery. They assess the overall delivery need and negotiate with elected representatives to ensure the resources will be available. The elected representatives likewise negotiate with their new regional governance body.

The community board understand and track needs in the community, the level to which they are being met and how delivery provision needs to change at an overview level. They are responsible for overseeing delivery, monitoring the effectiveness of provision and agreeing specific resource needs with each of the service provider organisations. They are also responsible for supporting the maintenance of effective organisational relationships between the service provider organisations.

Each service provider organisation including the local authority has autonomy within this governance structure and within agreements reached with peers to establish its own core purposes and identity. Local branches of larger organisations need to adapt their broader identity and purpose to local needs.

The organisations contribute their: transformation, delivery, management, monitoring, learning, strategy development and co-ordination skills and their team support mechanisms to the maximum in pursuit of meeting the community needs.

In this local community the Local Authority has decided to organise its staff into skill sets to maximise sharing of the learning coming from the multi-organisational and customer action teams. These skills groups also plan their own development based on their own learning from delivery and in conversation with the overall community board’s perceptions of what the future holds. They co-ordinate their staff’s assignments into action teams.

At the overseeing level, the local authority is taking strategic decisions and leading development and delivery of its capability to enable it to contribute fully in pursuance of its core purposes based on evidence being gathered by the multi-organisational action teams and intelligence from its own community environment and partners.

The shared responsibility removes the wariness of responding to the broader needs of those who approach them, reducing the risk of customer ping-pong with desperate customers being turned away because of budget cuts. The delivery partnership board takes responsibility for deciding how very difficult situations are addressed, with collective responsibility of an individual’s actions taking over.

How Might Customer Centric Action on Need affect Communities?

This post is based on the post on Customer Centric Action on Need.

Practical transformation is built on analysis of local needs and constrained by the sum of resources available to local public, voluntary and community organisations and the citizens themselves. Commitment and desire for change has to emerge within each community and its service providing organisations. It requires strategic design and agile implementation. This post is a work of imagination provided to illustrate what could transpire.

This post imagines how Customer Centric Action on Need would support transformation in society.

Customer Centric Action on Need is growing the competence of the widest possible range of organisations and individuals in the local area and encouraging them to step up and share the responsibility through team working at all levels. This has a significant impact on growing the community for all involved. Struggling carers, for example, benefit from understanding how they contribute to the team and value highly the support they get from other team members and on the job skills development.

The main challenge is to ensure timely and effective input to overall community strategy from all stakeholder groups, leading to ownership of plans and delivery. Public sector and many voluntary organisations have governance structures and relevant staff to engage in strategy within the community. Even the smaller voluntary organisations are likely to have a CEO for whom this is part of the job. This is less likely to be true of community self –help groups, caring neighbours, the customers themselves and their families, who provide a large amount of delivery for citizens with complex needs. For these people, their focus is tightly on delivery, because they do not have the spare capacity to engage. Because these are grass roots organisations and individuals, strategy emerges gradually from practice and learning. They have not been involved at an earlier stage, so are often uncertain what they think about new initiatives until they actually get to experience them.

Now that the local community addresses transformation in an agile way, these vital inputs and community ownership connections are tapped by community agile Customer Centric Action Teams which feed back into strategy. The community groups do not feel they are helpless implementers of other organisations strategy but significant owners with a voice.

This could be a real force for community transformation.

How might Customer Centric Action on Need Affect Citizens?

This Post builds on the previous post on Customer Centric Action on Need.

Practical transformation is built on analysis of local needs and constrained by the sum of resources available to local public, voluntary and community organisations and the citizens themselves. Commitment and desire for change has to emerge within each community and its service providing organisations. It requires strategic design and agile implementation. This post is therefore a work of imagination provided to illustrate what could transpire. This post imagines how Customer Centric Action on Need would affect individual citizens with multiple inter-related needs.

For complex situations, it makes sense from the customer’s viewpoint to discuss all their related needs with one person and decide with the help of their service providers how they wish to proceed and what actions they want to happen. An initial exploration of need can open up new opportunities for co-design of solutions, where personal initiatives from the citizen, support from family, friends and neighbours and public and voluntary sector services and community groups, can all be explored to address the unmet needs. This approach has a number of benefits from the customer’s viewpoint:

Support for the customer who does not know what actions are possible, which organisation they should approach and whether they are eligible for help. These questions are addressed in customer centric action on need, by understanding the inter-related needs and issues at the front line of the organisation the customer chooses to speak to:

In the public and voluntary sectors there are frequent changes to services and eligibility criteria. To the inexperienced, the hurdles in finding the right service and establishing eligibility can be significant and the system itself can be a major barrier to reaching help for those in need, particularly those who are not accustomed to asking for help.

Support for the customer with complex interrelated needs who doesn’t know which need to address first, and does not know whether addressing one issue may resolve others. In Customer Centric working, systemic methods and tools are adapted for efficient front line use and information capture:

Addressing deeper causes may obviate the need to address current symptoms.

Removal of the need for signposting and the need to ‘tell their story’ again. Addressing issues raised by uncoordinated service delivery. In customer centric working the delivery is based on an understanding of the connection between their needs:

With signposting, customers may get more services than they need and want. Customer centred planning enables their self-help capabilities to be valued and the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed solution to be assessed and the plan revised.

In the past a customer who had addressed one need would then need to return for their other needs to be diagnosed. A plan based on understanding of complex related needs at one time, addresses the full range of needs from a chosen start point.

Customers not only have current needs, they may also have fears for the future. Co-design gives them the opportunity to plan ahead for likely future needs and consider alternative strategies:

Linking development of future actions to customer ideas captured at the front line can be a powerful source of innovation. Understanding and capture of potential future needs and actions at the front line makes this possible.

Overall, the customer centric approach could lead to stronger engagement of citizens, family, neighbours and voluntary and community sector organisations in addressing an individual’s needs and increased skills in the community to handle these situations in future.

A vision of how Customer Centric Action could work

This post builds on the thoughts in the previous post on Customer Centric Action on Need

Practical transformation is built on analysis of local needs and constrained by the sum of resources available to local, public, voluntary and community organisations and the citizens themselves. Commitment and desire for change has to emerge within each community and its service providing organisations. It requires strategic design and agile implementation. This post is not a specific design but rather a work of imagination provided to illustrate what could transpire.

A by-product of producing and implementing shared action plans, is a set of complementary standard action components, collected and updated over time, to address the needs of a group of customers with a similar range of complex needs. This information is managed in the form of a guide indexed by needs, with identification of skills, profiles by role, contact details and eligibility and planning information. The guide supports co-design and planning of appropriate actions. The guide is updated by the action teams themselves as they learn.

Operationally these actions are delivered by individuals providing the activities identified in the plan (including the role of customer centred action co-ordination and monitoring), regardless of the organisational, customer or community status of each role player. This enables organisations to work within their budgets and customers within their competence, with team composition varying from customer to customer.

The total amount of resource from public, voluntary, community and customers clearly has to be adequate to meet the expected needs and this is established through stakeholder engagement in a joint planning process for each group of customers in the community. Shortfalls on skills are covered by planned background and on the job training, including for customers (or their advocates).

Customer Centric Action on Need enables electorates to choose to use more of or less of public funds to address citizen’s needs and to compensate for increases or reductions by providing less or more customer and voluntary and community sector action. Elected community representatives need to balance local needs against local taxes, other available funding and reserves and local commitments to payment in kind from the electors themselves, voluntary organisations, community groups and other separately funded public sector organisations.

Within each organisation, including the local authority, the plans for their overall skills and resource commitments are summed and managed within budget as skill related teams responsible for their own and multi-organisational action team shared learning and development.

Operations and management is overseen by the broadly representative community management team, supported by a resource bargain with the elected representatives.

Customer Centric Action on Need

The Impact of Service Cuts

At this time, local authorities need to reduce their spending whilst having little control over the amount of citizen’s needs they have a responsibility to meet. Whilst effectiveness and efficiency improvements and prioritisation of spend can help reduce costs, there is a risk that ongoing cuts may not only have a severe impact on community and individual quality of life, but could cause these citizens’ needs to escalate and emergency action costs to be incurred to the public purse, the individual and the community at some time and some place.

If local authorities perceive that cuts are reaching a point where budgets no longer meet essential needs, the choices would seem to be either, to find other ways to increase budgets, or to hand-over responsibility for meeting some of these needs to other people and organisations, perhaps through a combination of multi-organisational teams, self-help, friends, neighbours and the local community.

These posts introduce two contrasting paradigms: ‘Service Oriented Provision’ and ‘Customer Centric Action on Need’.

Service Oriented Provision

The public sector manages its customer relationships in terms of the services it provides and feedback from customers on the quality of its services delivered – referred to here as: Service Oriented Provision. In the Service Oriented model, the citizen accesses the service either explicitly, or via stating a need which guides the organisation to offer the service. Citizens with a number of needs are also signposted on to other service providers.

Whilst Service Oriented Provision works well to streamline delivery of straightforward requests, not all customer and public sector relationships benefit from being understood and managed as a collection of individually requested transactions. Service Oriented Provision works particularly well for customers with only one need at a time. It is not so effective for customers with complex inter-related needs, as no one service deliverer is addressing the whole customer within their particular environment or pulling together a plan to resolve their inter-related needs.

Customer Centric Action on Need

Customer Centric Action on Need is positioned as an alternative to the Service Oriented model for customers with complex related needs. It also provides a flexible approach to support migration to inclusive customer and multi-organisation team-working, which can adapt to changes in electoral decisions. The Circle of Customer Need approach was an initial exploration of this second paradigm (Customer Centric Action on Need) and this set of posts represents a development of the thinking.

Customer Centric Action on Need starts with the customer rather than the service. The service provider who is approached gains a picture of the complex inter-related needs from their customer; understanding what a beneficial change might look like and co-designing a solution which involves both the customer and potentially a range of service providers. The same approach is available wherever in the local community the customer makes contact: in person, electronically or by phone. The customer centred action is co-ordinated by one of the service providers (including the customer’s own plans) and its success is measured in terms of the quality of life of the customer. The quality of life feedback and service quality feedback, is firstly for the learning of the action teams themselves, including the customer, secondly for their respective organisation’s management and thirdly as evidential input for future strategy decisions and resourcing.

Aims of Customer Centric Action on Need

From a whole local area viewpoint, diagnosing needs and planning action at the front line creates significant efficiencies across the range of public and third sector providers. For individual customers, diagnosis of their set of related needs at the front line captures the essential data required to enable the action team member linkages to be made.

From a systems perspective, the ‘presenting’ need may not be the most effective need to address. For example: A refugee from domestic abuse might present with for example: a need for medical attention and or dentistry, a need for trauma counselling for themselves and their children, housing needs, ongoing security issues, a need to move children immediately to a new school given impending exams, a need for victim support through police investigation, emergency carer role cover for parents or neighbours, job loss or financial issues or many other specific needs. They may choose a public or voluntary sector organisation to ask for help, based on what they feel is the most pressing need and where they feel most supported. By having help to identify their competing and inter-acting needs, their emergency actions can be instigated and longer term decisions taken through co-design based on the broader view including self-help, community and family support and local service providers.

With Customer Centric Action on Need, gathering evidence of impacts over a range of similar cases provides evidence for future strategic funding decisions.

The realisation of Customer Centric Action on Need requires public and voluntary sector service provider transformation and local community transformation. It requires unstinted commitment to partnership working and practical initiatives to enable one organisation to act on behalf of another organisation, data that can be shared, appropriate skill development and adoption of common standards. It requires a coherent picture to be maintained of total locality action capability and action roles.

The customer-centric approach may act to uncover hidden needs at an earlier stage, but will also provide practical evidence for electoral decision taking on how the sum of these needs should be met.

There are also expected to be overall systems effects, whereby the savings from avoiding repeated customer interviews, sharing learning, coordinating action on need, making better targeted service selections, increasing innovation and taking higher quality strategic decisions would allow more front line service to be delivered with the same resource.

The citizen with the needs (or their advocate) is an active team player in addressing the issues (more than a service recipient), with opportunities to learn new skills and able to get the help they need.

A Workshop Based Approach to Building Organisational Identity or Culture

It is one thing to identify and agree the purposes of an organisation, but it requires another major step to flesh these out into a ‘fuller organisational identity’ which has significant buy-in from all the members of that organisation.

With a Viable Systems Model (Stafford Beer) mindset the organisation is a system in its own right within its environment and each internal stakeholder is also a system in their own right within their own environment, whilst at the same time these individuals collectively make up the organisation. The organisation is a composite individual, so, like the individual it requires an identity, so how is this built?

The concept of ‘shared values’ is great if it happens, but so often it becomes lip-service and inconsistent with observable behaviour. This is not surprising as each person has an appropriate autonomy, which for me includes their own value set within their own identity. So what if these individual value sets are not completely identical? It is unreasonable to demand that people change their own inner identity to match a set of values chosen by someone else and practically it won’t work.

A different approach from ‘shared values’ is to focus on ‘shared behaviour’. Each interaction and relationship within and on the organisation’s environmental boundary is strengthened or weakened by the quality of co-operation that occurs on an everyday basis. This is what turns a disparate set of individuals into a cohesive organisation and underpins effective customer / supplier relations – strong connections. This is not so much about a standard imposed behavioural formulae (e.g. the ‘have a nice day’ form of good-bye) as being aware of and responsive to the needs of those we need to co-operate with in a work setting.

Creating more effective ‘shared behaviour’ is something that can be addressed by a practical step. I had the opportunity to run a workshop for a small organisation, where every member, whatever their role was able to attend (with only a two or three attending part time). We used the world café approach of structured conversation on different tables with movement between tables, to enable conversations to interact and develop. Table groups explored their own needs and how they themselves would meet others’ needs. The discussion topics and table structure was informed by VSM to focus on the key organisational joins:

- external – operations to customers, partners and suppliers also competitor relations

- internal – individuals and teams,

- internal – individuals and managers,

- external – developing external relations for the future

- distilling – the sort of organisation it needs to be to achieve its stated purposes

This workshop didn’t change the organisation overnight, but it did surface a lot of improved understanding as a foundation for ongoing dialogues and monitoring of progress.

A key distinguishing feature of this workshop approach was its focus on working outside-in. How do our current customers and partners want us to be? Who will our future customers and partners be and how will they want us to be? How do we need to be internally with each other to be able to support and strengthen these external relationships? This acted to encourage creative thinking and avoid value based confrontation.

Fuel povery and vulnerable older people

Attempts to improve a situation, often result in unexpected and even counter-intuitive side effects. Some side effects may work very positively, but others may not. Thinking through possible chains of cause and effect (and particularly feed-back loops) can often flesh out many of such issues before the action is taken and this enables the proposals to be evaluated more fully before hand.

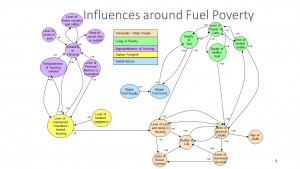

To think through possible impacts, it is vital to take a holistic view of the subject and consider how a broad range of inter-related topics affect each other. The diagram below is such an Influence Diagram. It shows a summary of interrelationships between different aspects of Fuel Poverty, gathered by reading a number of research papers on the topic and using the ‘Circle of Customer Need’ tool to look for any missing topics.

In the diagram, each arrow shows where one topic impacts another in terms of cause and effect. Arrows going both ways between two topics show a feed-back loop. Each topic is represented by a notional quantity, which will increase or decrease according to impacts within itself or from elsewhere. The title given to the topic focuses on describing this notional quantity e.g level of physical health. All arrows have a start and end topic and a +ve or -ve sign at their start. If an arrow has a +ve sign at its start, it means the end topic increases or decreases in line with the start topic. If on the other hand the arrow has a -ve sign the end topic increases when the start topic decreases and vice versa.

influence diagram of fuel poverty in older people

This diagram shows, reductions in physical health causing reductions in mobility, which can cause reductions in the quality of life, which can in turn cause reductions in physical health. This is often referred to as ‘a vicious cycle’. Alternatively improvements in physical health can improve mobility which can in turn improve quality of life which improve physical health – ‘a virtuous cycle’.

Such an influence diagram enables someone to explore the wider implications on fuel poverty in older people, of an action that they are planning to take, and in this way they can plan to handle any unwanted side effects. It can also show opportunities to magnify desirable impacts , or compare the effects of a number of options. The diagram can be improved with experience of use and further research or delved into in more detail, when useful.

A Sustainable Volunteering Relationship

In this post I describe a relationship between a third sector organisation and a volunteer and what factors lead to its sustainability. I characterise this relationship as more one of partnership than of hirer / contractor.

In such a partnership, I assume that both parties want:

- A productive and satisfying relationship, which will achieve both own and shared outcomes and so promote a relationship which endures

- To make effective use of scarce resources from both parties

- To provide good experiences which encourage third party recommendations of the organisation by the volunteers and so grow the organisation’s volunteering base

- To enable qualitative assessment of value created by the volunteering activity, based on a rounded view of all the stakeholders in the volunteering activity

- To promote ongoing development of the capabilities of both parties and organisational learning

Some volunteering relationships are specific and short in duration, whilst others last over many years. The lifespan of the relationship is often created and terminated by external events beyond the scope of the partnership (e.g. the volunteer moving away). A sustainable relationship is flexible and resilient to such factors, whilst being respectful to the needs of either party to terminate the relationship when they decide.

The Nature of the Partnership

A sustainable volunteering relationship is entered into and viewed as an ongoing partnership by both parties. Starting when both parties bring their needs to the table and home-in on a core activity or series of activities which meet their current needs and focus the partnership. If the experience is positive and the partnership’s external context continues to be supportive for both parties, then the core activity may, over time, become broader and grow to cover a wider range of activities which are valued by both parties. Alternatively the focus of the relationship may move, or be clarified and scoped down to deliver a narrower and more precise activity, or be terminated.

This highlights the need for ongoing shared review and learning about how the relationship is progressing and how it needs to change, including both external and future concerns and opportunities.

There is also a need for effective operational co-ordination, so that volunteers working beside other volunteers or employees can co-operate and collaborate around shared purposes and share their learning. The same is true for volunteer groups working beside other volunteer groups or employee groups.

As with any flourishing partnership between two organisations which are taking part in a joint venture, both parties:

- Focus on the common activities they are both motivated to undertake

- Identify with the purposes they share and own them, as well as their own other purposes

- Resource the activities at the level required to deliver the shared purposes that they agree to address

- Jointly steer the relationship so that it continues to meet their own needs and so that they can continue to resource the volunteering activities adequately, as the nature of the partnership evolves

The outcomes and measures enable both parties to distinguish successful strategies and identify what are appropriate types and levels of resources needed to achieve the desired outcomes.

The Viewpoint of Third Sector Organisation, its Purposes and Activities

The organisation identifies its overall purposes and identity at any point in time, aligned to today’s external and internal stakeholder needs and those of generations to come. This is reflected, for instance, in a publicly accessible vision statement or statement of stakeholder based objectives.

The organisation has different purposes aligning to different types of stakeholders. These purposes are understood at appropriate levels of detail, up and down the organisation, focused on the outcome responsibilities and related activities of the departments or teams involved. The organisation also has support and management functions, which enable the teams with outcome responsibilities to operate effectively.

The organisation, at all levels, identifies the ways in which volunteers could address (directly or indirectly) their purposes and so identifies suitable types of volunteer role(s).

Some roles are well understood and constrained to work in existing teams, whilst others are defined as a need to achieve an outcome, where the organisation needs the capabilities of the volunteers to help find ways to do it.

The organisation has its own strategy for attracting and deploying volunteers effectively. This strategy both constrains the strategies developed jointly with individual volunteers and is also informed by learning from the outcomes of such relationships.

The Viewpoint of the Volunteer

The volunteer assesses their own purposes and how volunteering fits into them. They match these against the organisations purposes and stakeholder needs and so identify the opportunities to contribute in different parts of the organisation. They consider their current capabilities that they can offer and areas of capability they wish to develop. They decide from this whether to and if so, how to engage with the third party organisation. They identify particular roles of interest, also taking into account how much flexibility is necessary to meet their own specific needs.